Jerusalem: The New, The Old, And The Future (Photo Reel)

Jerusalem has begun the proces of converting the historical King George Street (and Strauss, its northernly continuation) into a pedestrian and light rail only street (to make way for the under-construction Blue Line).

Adjacent to Ben Yehuda Street, King George is one of Jerusalem's central thoroughfares. Unsurprising (given its name) its inauguration dates back to the British Mandate period: the street was named in honor of the then-reigning King George V and attended by the leading political notables of the day, including Sir Herbert Samuel and Sir Ronald Storrs - the latter the Mandate's military governor of Jerusalem. The last time King George Street was repurposed was, literally, another era of history.

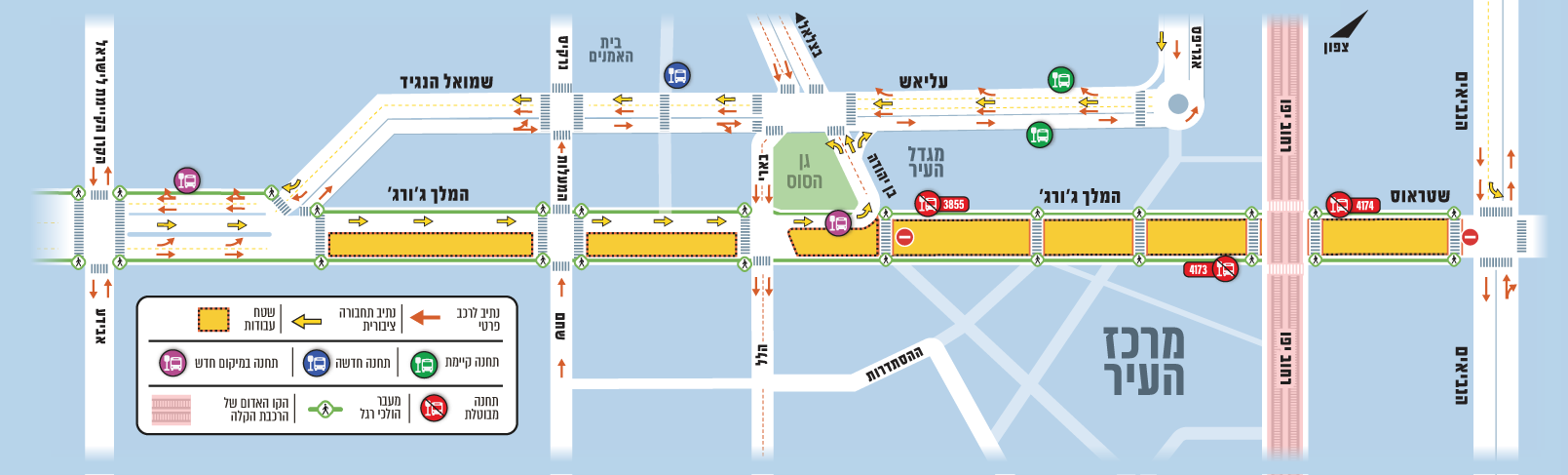

In the modern Jerusalem, of 2025, street changes no longer have to consider how horses and carriages can navigate around the chaos - but lots and lots of cars. As this traffic change diagram from the Jerusalem Municipality shows:

From the pedestrian vantagepoint: King George Street is now a vast open space of concrete with the familiar businesses lining either side of the roadworks (including the beloved Ma'oz Falafel and Shawarma from where this photo was taken):

Observing the huge concrete sections waiting to be laid in place, it struck me that - although we are inured to the sight of roadworks - much as those posing for photos during the street's inauguration were, we are watching history being made, again, in 2025.

The reuprposing of these central thoroughfares in Jerusalem - though it will undoubtgedly bring much short term noise and misery - bodes a better and more sustainble future for the city.

Although the exact metric is a little hard to pin down (the oft-cited claim that Israel has the highest level of per-capita car ownership, it seems, is a little mugzam) Israel certainly has an unsustainably high level of car ownership.

In Jerusalem - where nerves are often frayed to begin with - this finds auditory expression in the grating chorus of honking which the Municipality, and police - have been derelict in reducing. The chorus relents only on Shabbat and religious holidays.

Most drivers in Israel - and even most driving instructors, apparently - seem unaware of the fact that the gratitious use of the horn, as a conduit for releasing one's frustrations about the slow pace of traffic or life, is illegal.

Enforcement falls to the police who, especially in Jerusalem, have far more onerous and serious priorities: like thwarting terror, for one. Powers are derogated directly to the muncipality but simply having the power to issue fines to honkers isn't enough: reliable detection and evidence-gathering is needed such that routine prosecutions can be safely advanced. If neglected, the city risks bogging down resources in combatting a tidal wave of pettty litigtation from motorists insistent that this time they really needed to use their horn even if the AI camera (or inspector) thought otherwise.

Ultimately, the buck gets passed but citizens pay the collective price: noise pollution has been linked to elevated rates of hypertension and CVD making addressing this issue arguably not only a quality of life one but also a public health concern.

While I have been involved with an organisation advocating for this issue to receive more significant attention, I believe that the real solution to this problem will come from addressing it at root cause: we can use AI systems (etc) to detect and fine serial honkers. But we would probably be better served by finding less exasperating modes of transport for all residents.

In crowded spaces like Jerusalem, the answer has to be taking private cars off the road and making public transport more plentiful, efficient, and wide-reaching (my rant about the over-zealous and intimidating ticket inspection regime will have to wait for another day). Therefore I view the roadworks with a mixture of caution ("how long will they be digging this up?") and optimism.

A Sad Reminder Of Those Less Fortunate At Every Corner

Since October 7th, streetscapes around Israel haver been puncutated by tragic reminders of the fate of the hostages - urging passers-by not to forget those languishing in the tunnels of Gaza and for whom noise polllution is sadly the least of their worries. These take the form of individual hostage posters or more politicised slogans from The Hostages And Missing Persons Forum. The latter has adopted a strongly partisan and anti-government slant, frequently lambasting the government of Benjamin Netanyahyu for (they argue) not doing enough to bring the hostages home and for being intransigent during the lengthy negotiating process.

Some take the form of elaborate installations while others are campaign posters like this asking citizens, arrestingly, what they would do if a captive were their son?

All have the same objective: like the second poster urges, don't forget them.

The Sprawling High Rises Of Central Jerusalem

Every time I step outside my front door I am mesmerised by the sight of the high rise buildings which seem to be inching closer to the heavens by the day.

High rise construction in Jerusalem is a subject that is wrapped up in its own form of controversy - I happen to be married to an architect and urban planner who has her own strong views about this form of construction.

I am, however, simply a layman with a camera and an (uninformed) opinion. The sight of high rises has always made me happy and I've tried, once or twice, to explain why.

They evoke, for me, the vastness of city life: I believe that when lots of people come together (with lots of different talents and ways of viewing the world) humanity thrives. High rises can hold a lot of people - or at least it seems that way. So when I gaze upon a tall building I feel like my small contribution to the world, and my city, is part of a much bigger project.

They are polarising in the context of Jerusalem because they provide a fault line around which those with opposing visions for the future of the city congregate.

As mentioned, I'm firmly (though not without reservation) on the pro high rise side of the argument.

I want Jerusalem - as the capital of Israel and the Jewish people - to be every bit as industrious and impressive a city as Tel Aviv.

I want to see a Jerusalem that can provide economic opportunity and jobs for its citizens - and which doesn't laguish, perpetually, at the bottom of quality of life surveys.

I want to see a Jerusalem which also provides ample housing to house that sprawling population and think that if we can't build out (for reasons that are both geographic and political) that we should either build down or (more conventionally) upwards. I see Jerusalem as being at its best when the ancient and the modern fuse effortlessly.

My reservations to the high rise development in the city center more around how this housing stock is priced and who it's being marketed to:

If the housing is priced far beyond the budget of local residents and sold to investors or tourists who visit only around the Jewish high holidays then not only are none of those socioeconomic benefits realised, but resentment and profound inequality take their place.

We have seen far too much of this in the city already and learned that the main beneficiaries of this exercise are the developers who build these towers. The collective future of the city demands that we do not repeat these same mistakes.

Others see the preservation of Jerusalem's skyline - fending off the type of building that is now mushrooming throughout the city - as something akin to a religious duty. For them, Jerusalem must not resemble Tel Aviv: not only in its liberalism but also in its preferred mode of construction.

They believe that those green-lighting the high rises construction are imperilling the very essence of the city and react with anger at the very sight of the towers I've shared in this short essay.

The Kotel: Jerusalem's Beating Heart

I always found the idea of living in Jerusalem and not regularly visiting the kotel (the Western Wall) perplexing. How could you live (as a Jewish person) in a city that contains the holiest site in Jerusalem and not be drawn to go there at least once a month?

And yet oddly, over time, I've become exactly that person.

The reasons why many Jerusalemites don't make the pilgimage too often are, I suspect, rather mundane: life here is busy, there's shopping to be bought for Shabbat. And the kotel - indeed the whole of the old city - just isn't located in a part of town that you'd casually find yourself in after dropping by the accountant (or dentist).

There are other considerations, too: the old city is the flashpoint of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I may have lived through successive Iranian missile attacks, but there's something about the Old City that's especially unnerving: stabbing attacks are so regular that they're barely reported on internationally, they're random, gratitious, and there's no safe room to provide protection against them.

Although perhaps it's a reflection of my personality, I find the "coexistence" of the old city to be artificial, militarised, and inch-deep: waiting to rupture given the right set of religious and political tensions. I used to spend plenty of time walking its alleys (and visiting border regions that are today off-limit to civilians). Today I'm a good deal more reserved and cautious about where I go.

But the kotel is inspiring. And there's something about not visiting it habitually or casually that makes encountering it feel like a more weighty and momentous experience - as it should.

While there yesterday I said many prayers: for my new and growing family; for the Jewish people; for the safe return of the hostages and the welfare and safety of those fighting for them; for peaceful coexistence between Israel and the nations of the world, including our nearest neighbors; and for the future of Jerusalem: as a capital that is thriving, growing, and sutainable.